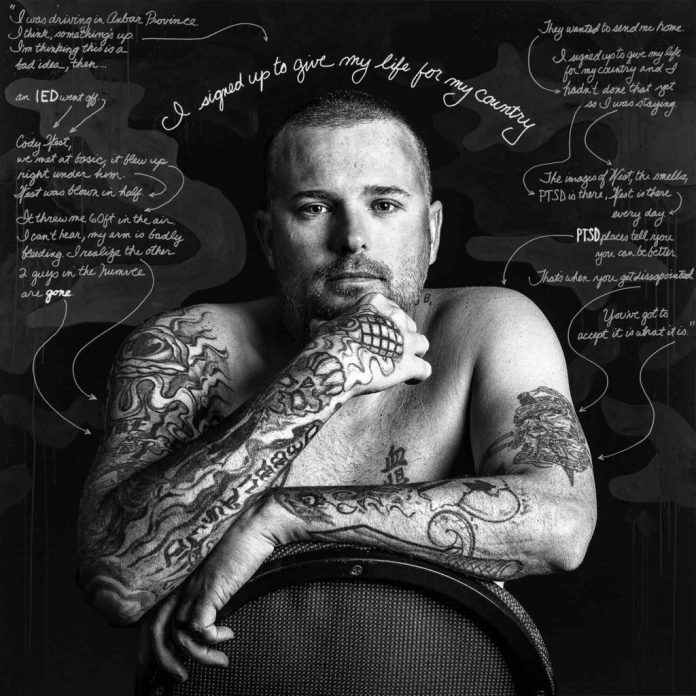

One of many worst nights of Susan Barron’s profession got here a number of years in the past, when the artist was in Manhattan to unveil her mixed-media artwork sequence, Depicting The Invisible. Navy veteran portraits adorned with paint and textual content comprised the gathering, which Barron designed to focus on veteran struggles with post-traumatic stress dysfunction (PTSD).

Simply earlier than the present, Barron’s cellphone rang. On the opposite finish of the road was the mom of one in all her photographic topics. “She stated he had succumbed to PTSD and brought his personal life,” Barron says. “It was a intestine punch.”

Almost three million service members have deployed in assist of the International Struggle on Terror since 2001. Of those that served in Iraq or Afghanistan, between 11 and 20 p.c now undergo from PTSD. These evident statistics have left an interminable path of suicide victims of their wake—people, like Barron’s pal, who quietly endure the invisible wounds of fight, private loss or sexual assault.

22 veterans per day. The suicide statistic has circulated extensively since such information first reached the general public sphere. In 2020, the Division of Veterans Affairs reported 6,146 navy vets died by suicide, an astonishing 17 per day. And whereas that quantity amounted to the bottom complete since 2006, any semblance of empathy would counsel it stands at 6,146 too many.

It was studying about this epidemic that impressed Barron to create “Depicting The Invisible,” an exhibit that, since its launch, has occupied the hallowed halls of the Nationwide Veterans Memorial and Museum in Columbus, OH, and the Military and Navy Membership in Washington, DC. amongst others.

“I’m actually grateful these very courageous women and men shared their tales with me,” Barron says. “I needed to shine a lightweight on this epidemic of PTSD and suicide and assist break down the stigma round problems with psychological well being. Each one in all us must do no matter we are able to to assist. As an artist, that is what I felt I may do.”

Barron’s photograph sequence was shot utilizing a classical black-and-white fashion that she says, “was deliberately in direct distinction to the brutality of their tales.”

“They’re heroic. They’re elegant,” Barron says.

The works additionally proved to be dialog starters, finally changing into the topic of an NPR podcast and an award-winning quick documentary of the identical identify.

“This mission has had so many arms carry it up, and all through all of it, I’ve been contacted by folks I don’t even know telling me what an enormous distinction it made of their life or of their partner’s life,” Barron says. “Sons, moms, grandmothers—so many members of the family have been grateful for destigmatizing this, for honoring this as a wound of battle and never a psychological sickness.”

Shattering stigmas has additionally opened the door to a extra expansive community of PTSD therapy choices for veterans, hashish principal amongst them.

Ryan Cauley might not be one in all Barron’s topics, however his story, just like the myriad of veterans enduring the trials of neurological trauma, is remarkably comparable. Initially from Pendleton, Indiana, Cauley joined the Military in 2004 and served as a cavalry scout till 2007 with the service’s 1st Squadron, thirty second Cavalry Regiment, one hundred and first Airborne Division.

Life after the service proved troublesome. Publish-traumatic stress impacted Cauley’s capability to attach. Despair and anxiousness grew to become a viciously cyclical norm. His angle and habits soured, and in flip, his marriage and private relationships eroded.

Months of anger administration and cognitive behavioral remedy helped Cauley perceive methods to handle the situation, but it surely wasn’t till his 2016 foray into medical hashish—and subsequent launch of the hashish and PTSD advocacy firm Fight Cultivators—that he’d expertise an actual transformation.

“I needed to persuade my spouse about utilizing hashish, however virtually immediately, she was capable of see the change in my angle,” Cauley says. “I used to be capable of give extra love and be extra compassionate. I may give attention to duties and never be consumed by damaging ideas.”

Noticeable angle adjustments finally manifested a real curiosity within the business, and in 2018, Cauley got down to full his first develop. “I used to be such a child,” he says, smiling on the reminiscence. “I needed to develop my very own hashish, as a result of, on the time, costs had been dearer than they’re now. At this time, we develop our personal as a result of it’s higher than something within the dispensaries.”

Cauley’s childish curiosity quickly blossomed right into a career. He grew to become a lead grower at an organization in Michigan, studying the ins and outs of large-scale development, environmental management and cloning. He even recruited his greatest pal from the Military, Carlos Ozuna, to work in the identical position. Collectively, the duo launched the Fight Cultivators Instagram account to be a car of contacting different veteran hashish advocates combating PTSD.

And whereas the chums have since left the corporate, Cauley credit the data the 2 collected there for the duo’s success with Fight Cultivators. Greater than that, nonetheless, has been the outstanding distinction hashish has made in Cauley’s private life. “It’s given me a lot of my life again,” he says. “That sense of doing one thing for a cause. It additionally gave Carlos and I the chance to work collectively once more.”

The variety of methods veterans are studying to confront PTSD is ever-expanding. For Barron and Cauley, utilizing their respective platforms has injected life right into a dialog about psychological well being that remained dormant for much too lengthy.

The dreaded cellphone name Barron obtained that day in Manhattan is one which lots of right this moment’s veterans and navy members of the family have endured advert nauseam. Each story is exclusive, however the excruciating ache of loss is undeniably comparable. Stopping that from occurring to anybody else, Barron says, is a calling we must always all gravitate towards.

“That day was a private low for me, but it surely ignited an excellent stronger drive to get these tales on the market,” Barron says. “All of us simply really want to do extra.”

This story was initially printed in problem 47 of the print version of Hashish Now.